Unsurprising code and magic — optimizing for the first time vs the nth time

I’ve read some recent back-and-forth on Twitter regarding whether “magic” in a framework or library is something to be avoided or sought. We’ve spent a fair amount of time over the past year rewriting the core of the Elix web components project to remove what we felt were magical aspects. I wanted to write down some reasoning for that, both to better understand my own instincts, and also as a way of explaining those changes in Elix.

Dealing with code to solve a problem more than once invokes two opposing forces in tension: 1) how much effort someone needs to invest to understand, read, or write something the first time and 2) the effort someone needs to expend to understand, read, or write that same something for the nth time.

We could represent the possible resolutions of this tension on a spectrum, where the left end represents optimizing for the first time and the right end represents optimizing for the nth time:

The Principle of Least Astonishment, also known as the Principle of Least Surprise, suggests that “a component of a system should behave in a way that most users will expect it to behave; the behavior should not astonish or surprise users.” This property sounds highly relevant to the left side of the spectrum. We could characterize that end as “straightforward” or “unsurprising”; it also tends to be “flexible”. A negative characterization might be “verbose”.

On the other end, positive characterizations of the right end of that spectrum might be “concise” and “efficient”; negative characterizations might be “surprising” or “hard to learn”, and possibly “inflexible”.

Programmers evidently disagree on a definition for “magic”, but when I find code I personally consider to be magic, it’s at the right end of this spectrum.

Let’s walk through some examples of how an identical bit of functionality might be expressed at different points along this spectrum, working our way from left (first time, unsurprising) to right (nth time, potentially very surprising).

Suppose we have a class Foo that wants to log a message “Hello” in its constructor, and the output should be “Foo: Hello”. (Let’s take it as a given that we want to create a class; if all we really want to do is log a message, we obviously don’t need a class.)

A completely straightforward solution at the far left end of the spectrum:

class Foo {

constructor() {

console.log("Foo: Hello");

}

}

To a JavaScript developer, there is zero surprise in this code: it’s all standard JavaScript syntax and a single call to a well-known web platform API to log a string. When they run this code, the resulting console message will be 100% expected. This code is also completely flexible: if the developer wants to change the message, or log two messages, or whatever, they have the freedom to do so.

In this trivial example, we could easily decide we want to stay on this unsurprising side of the continuum, and ask everyone on our project writing one of these classes to copy-and-paste this boilerplate into their code. That’s an eminently reasonable answer.

But maybe our little logging task gets more complex, and the amount of boilerplate creeps up to a few lines, or a dozen. In that case, we might want to factor things out. We want to trade off a tiny bit of conceptual load for brevity. We begin to consider how much support we want to give ourselves for writing this code for the nth time. We feel tugged along to the right of this spectrum.

If logging begins to entail some complexity, we could create a utility function to log our message:

import log from "./log.js";

class Foo {

constructor() {

log("Foo: Hello");

}

}

This has the potential to be ever-so-slightly surprising to a new project member. They’ll be told to use the boilerplate, but they can’t be completely sure what log is going to do unless they read the source. We’re relying here on the obviousness of the library function name “log” to eliminate or reduce surprise. If we choose our name well, a dev will be able to imagine what the API will do. In the above case, seeing a console message will not be surprising.

There may come a point where we have other requirements for our classes, and see the introduction of a number of other API methods our devs should remember to call. We could introduce a bit of framework for these classes in the form of a base class to provide those APIs:

import Base from "./Base.js";

class Foo extends Base {

constructor() {

super();

this.log("Foo: Hello");

}

}

The functionality is equivalent — although we’ve introduced a potential for a great deal more surprise because the constructor needs to call super. That could be helpful; there may be useful initialization the Base superclass can provide. Significantly, some of that useful functionality could be added to Base in the future, and the Foo class here would benefit even if its code were left unchanged.

The tradeoff is that our class author now has a bit of framework under their feet, and may be a little surprised what it does, especially if that behavior changes underneath them without notice.

If devs on our project occasionally forget to call this.log(), one recourse would be to move the logging call to the superclass, and have the subclass pass the message-to-be-logged to the super constructor:

import Base from "./Base.js";

class Foo extends Base {

constructor() {

super("Foo: Hello");

}

}

If we’re using a type-checking system like TypeScript, we can define the signature of the Base class constructor such that the message is required. In that way, if the dev forgets to pass a message, or forgets to define a constructor entirely, the type-checker will produce a compile-time error. That should serve as an effective reminder.

That’s a powerful degree of enforcement — but note that we’ve lost some of the clarity of our code. That string parameter to the super constructor has no obvious identity or purpose. When the superclass logs that message to the console, that could easily surprise the developer.

Another point worth noting is that our solution is now less flexible. The downside of requiring a string parameter in the constructor is that the developer must always supply a string. If they don’t want to log a message, or want to log two messages, etc., they’ll have a harder time figuring out the best way to do so.

We could restore some clarity by introducing a property which the base class constructor will retrieve from the subclass:

import Base from "./Base.js";

class Foo extends Base {

get message() {

return "Foo: Hello";

}

}

Although the purpose of the string is now a bit clearer — it’s a message of some kind — its involvement in the class is quite unclear. From the above, it’s not apparent whether the message code gets called at all.

The message property is essentially a new lifecycle method defined by the Base class. That’s a powerful technique, but the timing and behavior of a lifecycle method are opaque unless one reads the documentation. It’s unclear, for example, when that property will be retrieved, whether it might be retrieved once or multiple times, whether it should return the same value each time, whether the value will be cached, etc.

One thing we may notice as our team copies-and-pastes this boilerplate is that people may occasionally forget to update the name of the template class “Foo” in the message string. To address that, we could have the Base class itself obtain the class name from the subclass using reflection, e.g., by retrieving this.constructor.name.

import Base from "./Base.js";

class Foo extends Base {

get message() {

return "Hello";

}

}

This is more concise, but when the class logs “Foo: Hello”, it may take the dev a minute to figure out where the “Foo” part came from. That’s possibly surprising.

What will be extremely surprising is compiling or minimizing this class and discovering that it logs something like “a: Hello”. Build tools may transform source code, including class names, so the class Foo might be renamed a for brevity. This interference between library abstraction and build tools can often be baffling, especially if you’re familiar with only one layer or portion of a complex system.

If our team is writing dozens of these classes, we might decide to optimize for brevity even further. We might decide to use still-unstandardized JavaScript decorators, say:

import Base from "./Base.js";

@message("Hello")

class Foo extends Base {}

This is quite concise. In exchange, it’s also quite limited. For one thing, since decorators are not yet standard JavaScript (as of this writing), we’re forcing the project to use a transpiler to process the decorator.

For another thing, depending on how it’s implemented, the decorator may run with different timing than the earlier message getter. The decorator is also more constrained than a handwritten property getter. Depending on the size of our project, we might decide that such constraints are beneficial — or we might discover that they place significant limitations on a developer trying to handle edge cases.

[Update: @pmdartus pointed out that the message decorator would have to be imported from somewhere.]

Suppose our team is now writing hundreds of these classes. Maybe those classes are now directly related to our company’s core business, and we make money for every class we write!

We could create a domain-specific language just to crank these classes out. We could, say, define a JSON format, and put the following in Foo.json:

{

"message": "Hello"

}

And then have a build tool consume this format to generate a class with the name and message we want. That’s extremely efficient, but it’s getting pretty hard to tell from the above what’s going to happen. This also requires a new developer to install and learn a proprietary tool, which is going to drive up the time required to write their first class.

And the result is now quite rigid: since there’s no place here for the dev to contribute code, there’s no ability for them to accommodate unusual situations.

Why stop there? Let’s define a new file format that contains nothing but the message we want to log, and take the class name from the name of the file. We create a new file called Foo and put the message into it:

Hello

We compile this to generate a class, run that, and see “Foo: Hello” in the console. Was that expected?

We’re working at a theoretical edge now, as every bit of information is tuned to our task. We’ve got a system that’s highly optimized for our needs. You may have a different definition for “magic”, but this solution feels pretty magic to me.

This solution is probably quite surprising to the uninitiated. The line of “code” above certainly looks simple, but it’s impossible to guess what it will do until you run it.

The solution would be extremely efficient for teams that need to crank out these classes, but the solution is also completely rigid. It can’t do anything other than what it’s designed to do.

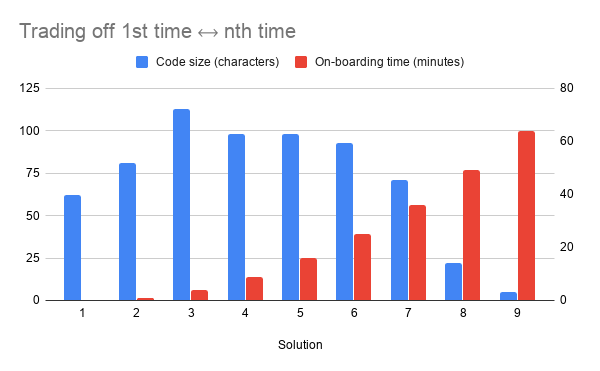

We can do some simplistic analysis of these solutions. For starters, while code size doesn’t equate directly to nth time efficiency, it’s a reasonable proxy. We could assume that having to write less code for the nth occurrence means being more efficient over the long term.

It’s rather more difficult to represent the on-boarding work required to be able to read or write the code the first time, which gets to the very appeal of the left end of the spectrum. For the sake of argument, I imagined an exponential increase in the time required to get a new developer on board: the minutes required to read docs, install and learn build tools, ask questions when things don’t work, etc.

This representation doesn’t capture everything.

This entire example is contrived, but surely there are correlations at work like this whenever we’re resolving the 1st time/nth time tension.

Significantly, that tension applies to reading and understanding code, not just writing and maintaining it. A solution at the left end of the spectrum might entail more code then one at the right end, but a new developer should be able to more readily understand what code at the left end does and how it actually works.

I think it’s interesting to consider this spectrum through some analytical lens. Surely we could take a more data-driven approach to assessing where we are — and deciding where we want to be — on this spectrum.

Positions along this spectrum are not objectively good or bad — it depends on what you’re trying to achieve and optimize for.

In the case of the Elix project, we want to optimize for: a) a large audience of professional web developers that can quickly understand the code, and b) a high degree of flexibility. We want people to build a wide range of solutions with the project’s web components, so we prefer to preserve flexibility and possibly sacrifice nth time efficiency. In other words, we deliberately target the left end of this spectrum.

As a case in point, we recently deprecated an Elix helper function that manipulated a web component template in a particular way. The helper allowed for efficiency, but was novel, and we ultimately felt that it wasn’t all that much more efficient than calling the underlying DOM API directly. We’d prefer to just encourage developers to call a DOM API they already know extremely well. We may someday feel that we understand the problem space better, and decide to better support nth time use by adding back such a helper, but for now we’re happy to keep the Elix code unsurprising.